Friday the 13th — a fitting day to talk about Coraline.

The movie, directed and written for the screen by Henry Selick, is an infectious romp with some truly spectacular set pieces. Depending on how audiences react to the darker aspects, it’s sure to become either a cult or mass favorite. But very early on came that familiar twinge of kinda wishing I hadn’t read the book.

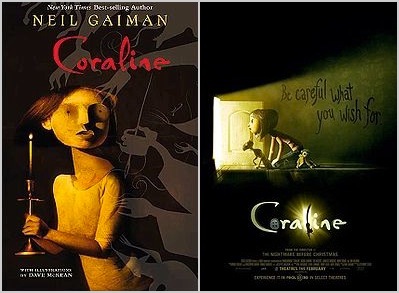

Written by Neil Gaiman, and the winner of a Hugo among other awards given to science-fiction, horror, or fantasy works, Coraline the book was good. The problem is that, as prose fiction will do, it calls heavily upon the reader’s imagination to illustrate Coraline’s worlds, aided by Dave McKean’s cover and occasional black-&-white interior art. Gaiman and McKean broke into the American comics market together over 20 years ago with Black Orchid for DC, and McKean produced covers for Gaiman’s landmark series The Sandman. Having collaborated on several graphic novels and picture books — long before Gaiman was “Neil Gaiman, Bestselling Author of American Gods” — they more recently made the film MirrorMask, which I now really want to see. Although I didn’t remember much about Coraline the book in great detail, I quite clearly remembered McKean’s illustrations, and they decidedly aren’t the basis for the look of Coraline the movie; not a complaint, but still inevitable baggage. [Update: I forgot to note that P. Craig Russell adapted Coraline to comics, as published last year, in a different style entirely.]

I also remembered that the book was dark. And the film, while not as dark, is indeed rated PG. We’re talking about a girl with inattentive parents who’s moved to a new house (a very familiar trope in children’s fiction) and soon discovers that she can visit a magical world with much friendlier, cooler, and more, well, magical people and things than exist in the dreary world she leaves behind, but of course staying there will come at a terrible price. My 6-year-old niece could probably handle it, albeit not without a grownup in the next seat for reassurance; my 4-year-old niece could not — yet there were tykes being walked and even carried by their parents into the theater, only to be walked or carried out when the going got spooky. Did Mom or Dad not catch one ad, clip, or review that alluded to the movie’s wicked witch wanting to sew buttons onto Coraline’s eyes?

My viewing party saw the 3D version of the film. It was my first experience with the newfangled glasses, which are tinted but not colored red/green or red/blue like the old days, allowing for the movie itself to be in color. And we were lucky to sit next to a whole family with kids who loved the film, none more than the mother — she not only laughed freely, but pointed at the screen in delight. I recommend the 3D despite the fact that it’s still a gimmick that carries the drawback of reminding you that you’re immersed in artifice at the same time it impresses you. The glasses do make the screen image dimmer, but it’s possible that the brightness of the screen was turned up to compensate for this as it was surprisingly vibrant when I peeked out from under them; in any event, Coraline is a story that calls for a certain amount of gloom.

The film was preceded by an extended trailer from an upcoming Ice Age movie that effectively worked as a stand-alone short. I haven’t seen a single one of those, but I recognized Skrat, who here gets into a winning Pepé Le Pew adventure to the strains of personal fave Lou Rawls.

I’ve enjoyed stop-motion animation from Wallace & Gromit to such Rankin-Bass TV classics as Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer to Henry Selick’s own The Nightmare before Christmas (at first developed and subsequently produced by Tim Burton — then marketed as Tim Burton’s The Nightmare before Christmas, which somehow led more than a few news outlets to erroneously tout reviews of Tim Burton’s Coraline). Early on, though, Coraline looked so fluid to me that I assumed CGI was involved — not that CGI is renowned for its fluidity; it’s just that stop-motion is almost inevitably a little jerky and I figured computers were used to smooth out some transitions — but the filmmakers have said that the only digital work performed was erasure of wires and such, as is done for stunt sequences in live-action movies. The movements of the characters also looked exaggerated, as if they were projecting to the back row, which combined with the overexpressiveness of some of the voices began to deflate my enthusiasm for the film.

Either the movie changed as it went on or my perceptions did, however, for I found myself completely enraptured no later than a third of the way in. There is joyous visual inventiveness that would not have been possible with the spare, black-&-white art of the book. While the story echoes The Wizard of Oz and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in its colorful neighbors and alternate-world travelogue, Coraline’s ability to travel back and forth to the bizarre home of her Other Mother and the tragic fate that may ultimately await her there recall the darker fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm — Coraline isn’t offered a secretly poisoned apple; she’s asked to willingly give up her eyes, and that’s not even the twist.

The score deserves special mention as a winner from start to finish. Composed by Bruno Coulais, it also features a new song from They Might Be Giants performed in the film by the Other Father.

Dakota Fanning does a fine job as Coraline, but it’s a shame that most animated films today cast movie or television stars instead of professional voice actors in leading roles (even smaller-scale films, often as a condition of financing). When mannerisms and facial characteristics are based on the stars in big-budget animated comedies, this works nicely, but here those who know John Hodgman from Mac-vs.-PC commercials or The Daily Show have to adjust to his voice coming from the lanky frame of Coraline’s dad — and Teri Hatcher’s character only resembles her towards the end, in what’s hardly a flattering comparison.

On the other hand, Ian McShane disappears into the role of Mr. Bobinsky, mouse-circus ringleader, who looks like a Russian cousin to the Blue Meanies of Yellow Submarine, while Dawn French and her Absolutely Fabulous partner Jennifer Saunders — whose show-stopping rendition of a terrible song was nearly the only thing I liked in the first Shrek sequel — voice Coraline’s spinster neighbors Miss Forcible and Miss Spink. Most bewitching is Keith David as the voice of the Cat, who sounds for all the world like a seductive Esther Rolle. The less said about Wybie, a boy invented for the film so that Coraline would have a reason to speak aloud onscreen, the better, although he provides a bit of effective pathos early on in the Other Mother’s world.

Some of my favorite films have isolated creative misfires of significant magnitude that keep them from perfection, but usually they let me down near the end instead of the beginning as did Coraline, which grew in my estimation considerably. I recommend it to everyone open to fantasy or innovative filmmaking, nearly worth the price of admission for the schnauzer bats alone.

Coraline book-jacket art © 2002 Dave McKean. Coraline movie still and poster © 2009 Laika.

Related: Braids of Glory • Flow Rider • We Got a Live One

Here • Ghosts in the Machine • Bedtimes and Broomsticks