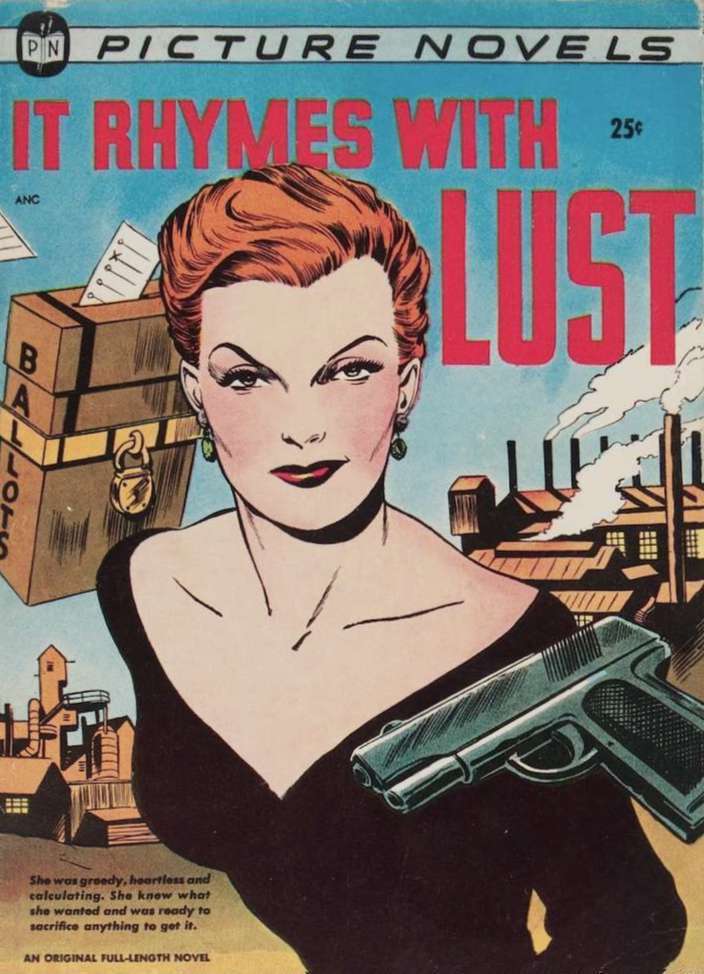

St. John Publications began its short-lived “Picture Novel” line, blending the comic book with the somewhat more respectable and certainly more adult entertainment of the prose paperback potboiler, in 1950. It Rhymes with Lust was a digest-sized volume, black-&-white interiors under a color cover, sold on newsstands for 25¢. Dark Horse Comics released a replica edition in 2007.

The honeys are Rust Masson and her stepdaughter, Audrey, vying for the affections

of our protagonist, Hal Weber.

The guns come out in the climax of the book, when all the principal players converge upon the Masson Mining Company.

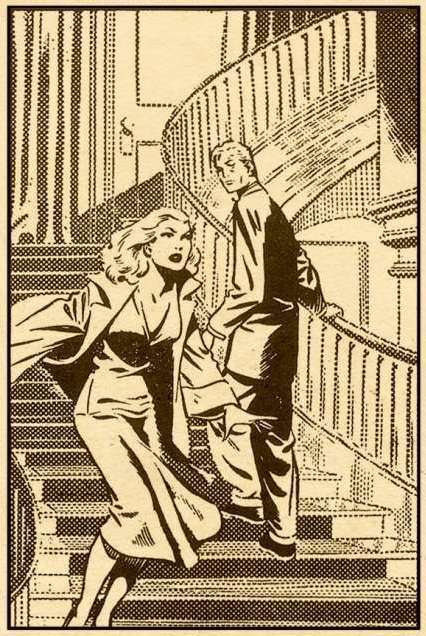

The foyer is barely seen in the home that Rust shared with the late Arthur “Buck” Masson, but crucial, as it’s where Hal first glimpses Audrey on his way to visit his newly widowed old flame, completing the labored Warren Zevon pun.

Arnold Drake wrote It Rhymes with Lust with Leslie Waller under the pseudonym Drake Waller. If Julius Schwartz was sort-of the ’60s DC equivalent of Marvel editor Stan Lee, as I put forth last week, Drake was definitely the ’60s DC equivalent of Marvel writer Stan Lee. He wrote imaginative sci-fi stories and co-created the angsty Deadman and misfit Doom Patrol, the latter’s debut in My Greatest Adventure hitting the racks nearly simultaneously with the first issue of the very similar X-Men. That, however, came well after Rust Masson.

In his afterword to the Dark Horse reissue of Lust, Drake traces the history of stand-alone, grown-up comics in an impressively brief, accessible fashion, arguing not too immodestly that he was ahead of his time. Drake & Waller were attending school in 1949 via the GI Bill and writing comic books on the side when he realized: With all the other returned soldiers in his position, accustomed to picking up panel-to-panel fiction at the PX, there could be a market for, as Drake puts it, “stories illustrated as comics but with more mature plots, characters, and dialogue”. He pitched the idea to St. John, a small but historically significant comic-book and magazine publisher, with his own rudimentary drawings.

Crossing the popular crime and romance genres, which along with tales of horror, Westerns, and other non-costumed adventuring were supplanting superheroes in comic books as the 1950s dawned, It Rhymes with Lust strikes me as a curious choice for an opening bid to attract the attention of freshly minted veterans — more what you’d find on the Lifetime channel if it existed back then and less Double Indemnity. Of course, I’m a habitual comics reader fifty years in the future of that postwar audience, so I may be ascribing stronger genre-related gender (or gender-related genre) preferences to that era than warranted.

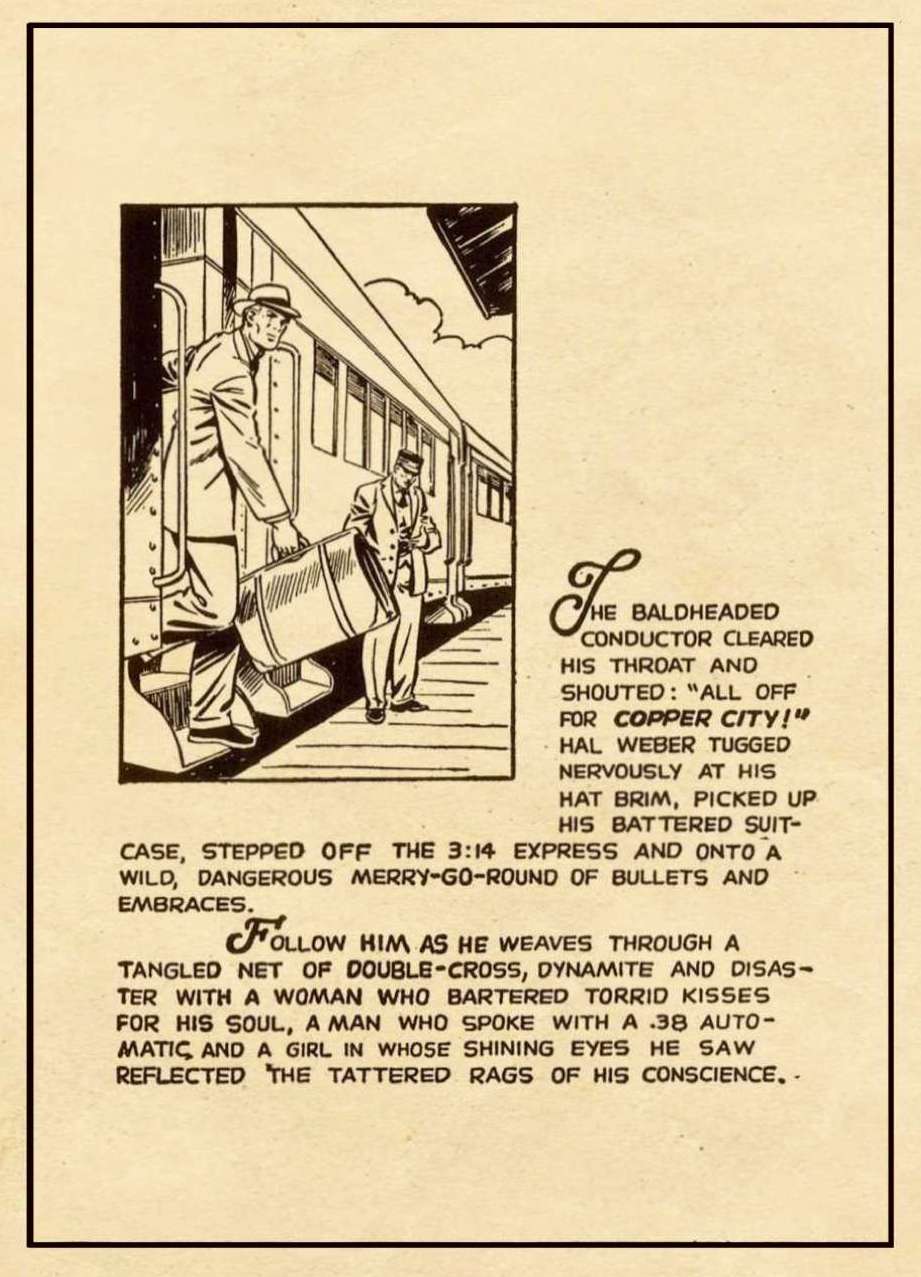

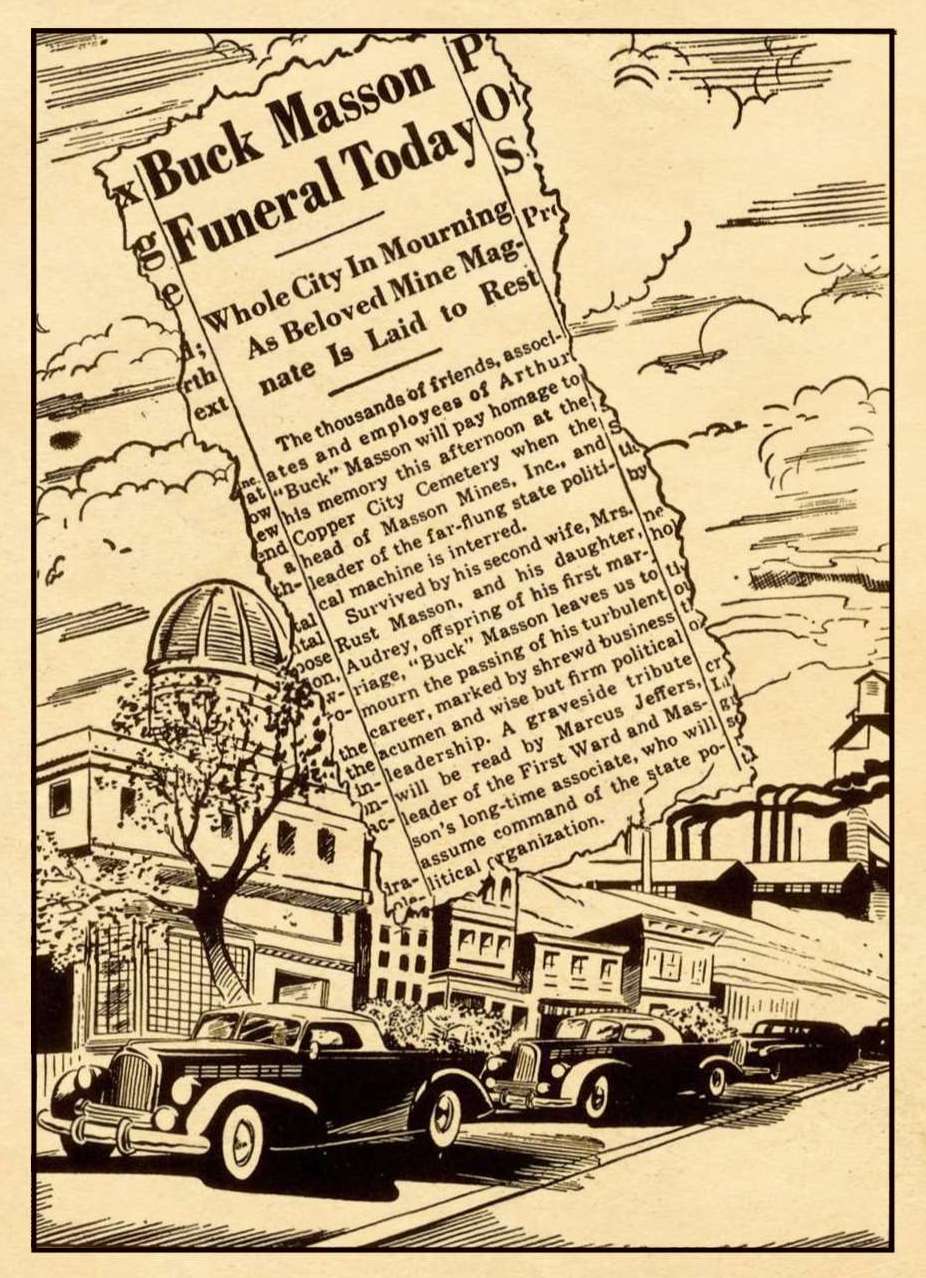

First [enlarge], second [enlarge], and third [enlarge] pages of It Rhymes with

Lust © 1950 St. John Publishing. Script: Arnold Drake & Leslie Waller.

Pencils: Matt Baker. Inks: Ray Osrin. Lettering: Unknown.

One thing that the narrative does quite smartly — and which reinforces my feeling

that Lust is as much a book to introduce prose readers to comics as to bring comics readers more adult material — is ease itself into the panel-to-panel continuity. The first story page has one small, boxed illustration surrounded by narration rendered in some of the tightest hand lettering you’ll ever see. We then get a full-page illustration, but with a printed newspaper clipping pasted atop it. Following that a wordy caption kicks off the first multi-panel page. Whether or not this was intentional on the part of the authors or publisher, it acts as a sort of prose-to-comics decompression chamber.

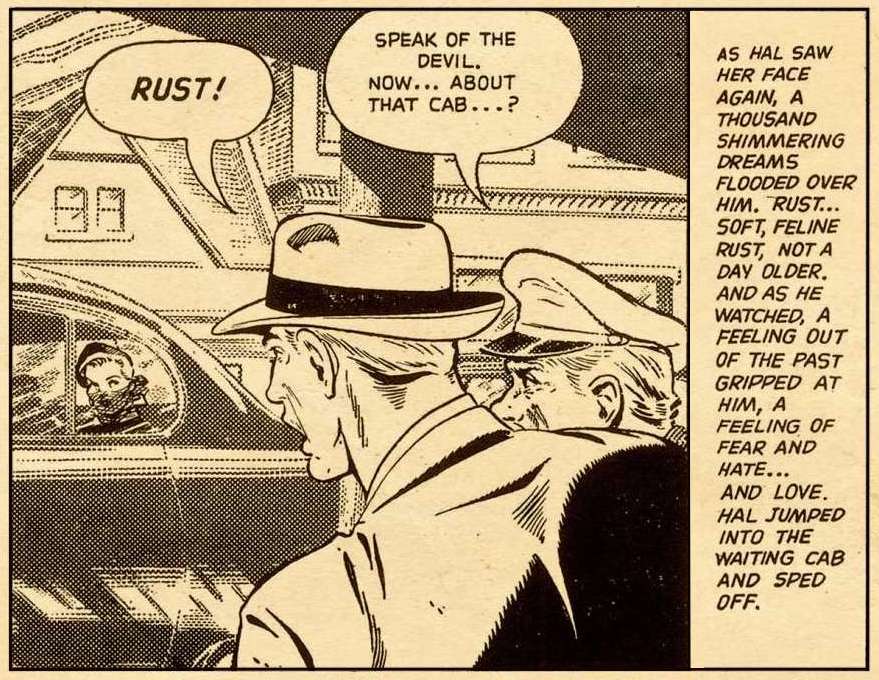

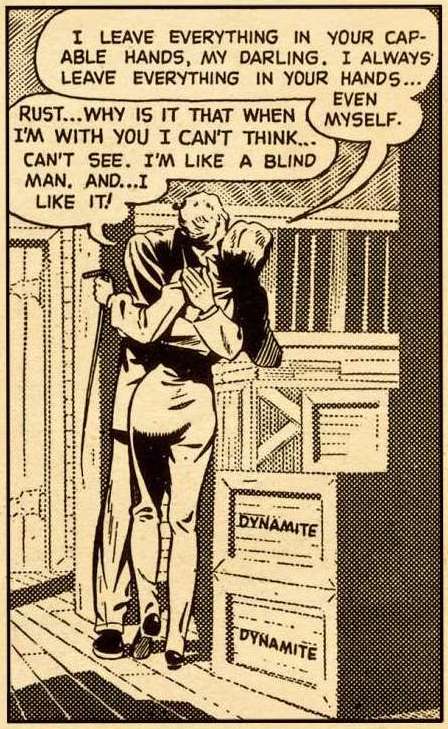

As the story opens, Buck Masson has just died, leaving his second wife, Rust, and his lieutenant, Marcus Jeffers, in conflict over the operation of not just Masson’s business affairs but the “state political machine”. Hal Weber arrives in Copper City to meet with Rust, who reveals that she summoned him there to take over the city’s opposition newspaper. Everyone knows that the Massons own The News-Times, but they own the anti-Masson Express, too, which Rust wants Hal to use to undermine Jeffers. Once a crusading idealist, Hal is now cynical yet still naive, his qualms about reporting to Rust instead of reporting the truth dissolving whenever he’s within twenty feet of her womanly wiles — at least until the escalating violence and the lure of young Audrey Masson, daughter of Buck’s first wife, begin to change his mind.

Penciled by Matt Baker and inked by Ray Osrin, It Rhymes with Lust is generally handsome. Whatever debits it may incur in stiffness, by today’s standards, are more than compensated by the period charm that very stiffness brings. Baker was renowned for drawing lovely ladies in action features, notably Phantom Lady and Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, and while occasionally uneven the illustrations in Lust are on the whole crisp and detailed, printed in the Dark Horse edition on sturdy paper with just a hint of grayness in the vein of old-fashioned newsprint.

Duoshade or a similar technique is used throughout the book in a largely counter-productive way, my one real artistic complaint. It’s usually applied in lieu of stippling or crosshatching to fill in an area that should be darkened but not solid black, as well as to lighten the linework of the background and so provide contrast as it is here. The problem is that Lust deploys it to echo a photographer or filmmaker’s manipulation of focus in a disconcerting way that often gives us a sharp plane unnaturally sandwiched between two blurred ones or, as in the panel above, the other way around.

It Rhymes with Lust is ultimately a historical curiosity, but a welcome one that can be enjoyed as period melodrama. The hero dithers until it’s almost too late, undying love is professed at the end of the first chapter after one night of dancing, and you nearly root for the villainess because even though she’s a witch she’s the most determined character in the story. You’ll find soap-opera poetry in such full-page, silent shots as Rust in an amorous embrace with Hal the day her husband was buried, surrounded by his portraits. And even though this Picture Novel often opts to tell when it could show, sometimes the overwrought prose is the only deliciously florid way to convey the characters’ emotions, all the more fun when it clunks now and then.

St. John gave up on Picture Novels after just one more book in 1950 from another creative team. The Case of the Winking Buddha was billed as an “Original, All-Picture Mystery” and has yet to be reprinted. While that and Lust would have cost you a quarter apiece on the newsstands, Dark Horse’s replica edition retails for $14.95. [Update: The Dark Horse reissue is now out of print. As the copyright to the original publication has lapsed, other editions can be found, but quality of reproduction and supplementary material will vary. You can also read an online scan at the free public-domain library Comic-Book Plus.]

Related: A Body Eclectic • Five-Panel Draw • His Story

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteWhat makes you think that pulp novels were "somewhat more respectable" than comics? I always had the sense that cheap sexploitation fiction was pretty close to the bottom of the barrel. But I was born in 1967, so my instinctive sense of these hierarchies isn't necessarily very accurate.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteI was born in 1970, Henebry, so our perspectives are probably pretty similar.

The remark came in large part from a general sense over my lifetime — certainly the first 15 years or so — that while trashy prose might be dismissed as escapist at best and for lesser minds at worst, comics were often used in TV or movies to indicate someone was not merely juvenile but literally an imbecile if not (never mind the contradiction/paradox) outright illiterate. Arnold Drake's afterword speaks of making comics more adult by infusing the medium with this potboiler melodrama, so at least implicitly (if not explicitly, although I think so; I haven't reread it in a few years) his aim is to make the largely short-story, periodical, pictoral medium of comics more adult by (re)grafting the pulp-novel feel onto it. I've quoted him in the piece as proposing "stories illustrated as comics but with more mature plots, characters, and dialogue"; of course, "mature" and "adult" have dual and almost divergent connotations of classiness when it comes to sex in particular.

I should point out too that I do qualify "the prose paperback potboiler" as "somewhat more respectable" [emphasis added here] and use the contrasting phrase "certainly more adult".